Yoga: The Evolution of a Sacred Philosophy

by Andrea Fulkerson

Originally written as an assignment for professor Daniel Simpson at Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, July 2022.

One of the beautiful qualities of being in a body is that it changes. From the time we are born, until the body dies, our physical and mental capacities are altering, but somewhere within the depths of our being we remain ourselves. This is clearly evident when you meet someone you have not seen for a long period of time. They have changed physically, but within the framework of who they are they are still recognizable. In human language, we call this ‘aging’. If we live long enough, we may gain the wisdom to know that there is something solid around the changing external.

When one delves into the ancient Hindu texts to gain an understanding of Yoga, we see that core in yoga comes from one of the several meanings of the word: to unite, and a realization of connectedness. When humans were in small hunting and gathering groups, connecting with oneself, each other and the world was natural; survival depended upon it. However, once civilization began, the business of life became more complex and humans lost sight of their identity. Historically, and even today, those humans seeking liberation from the business of life can gain divine insight through knowledge such as the Vedas, or by sitting near the feet of a teacher as in the Upanishads.

Most contemporary students of yoga have encountered the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali; a book of aphorisms considered the primary yoga text, but other ancient texts such as the Shvetashvatara Upanishad, the Mahabharata, and the Bhagavad-Gita, are also important in the exploration and together are called classical yoga. Patanjali’s work, the most known in yoga circles, discusses the stilling of the mind as its primary message. Indeed, the quieting of the fluctuations of consciousness is the reason for the entire text! To do this, he says, seekers must disentangle the spirit from the material prakriti.

If Patanjali, and earlier classical yoga texts, teach students how to calm the storm of mental activity by separation, how did yoga become known for its postures, and does this mean that modern yoga is inauthentic because it does not properly reflect Patanjali’s teachings on yoga? The answer is somewhat of a paradox, and typical of how Hinduism has aged gracefully by shifting, changing and expanding on the original message of the ancient texts.

Historically, differing ideas were discussed and vigorously debated, and some concepts were incorporated into the core philosophical teachings if they were seen to be practical; morphing while staying intact. This can be seen in the beginning of the yoga teachings, when Patanjali’s yoga and the Samkhya doctorine were virtually indistinguishable; both were methods of reaching the goal of liberation. For eg. Krishna states in the Bhagavad Gita (BG), “Foolish children say the Samkhya and yoga are different, but not learned pandits. A person who properly adheres to one of these paths gains the fruit of both”. This idea is mirrored in the Mahabharata where Yudhishthira’s grandfather says that followers of yoga base their conclusions on direct perception whilst the Samkhyas are guided by scripture, but both systems teach the truth. Even though they had different names, the endpoint of both systems were the same.

Initially, yoga was linked with Samkhya. However, in recent times, yoga has been related more to Vedanta. There are slight differences between the systems, but both systems, and indeed Patanjali’s as well, share the aim of delivering the soul from material embodiment, thus setting it free from repeated births and deaths. In order to break the cycle, a person must understand and gain knowledge of the truth of her own identity. This identity can be summed up in Vedanta as “aham brahmasmi” or “I am without qualities”.

Sutra I.3: Then, the seer dwells in his own true splendour.

BKS Iyengar (Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali)

Similarly, Patanjali speaks of the witness existing in its true identity in sutra 1.3 as well as liberation from worldly suffering in the second pada (2.18-27). It is clear that in the earliest texts on the subject of yoga, the focus was on the restraint of the mind (sutra 1.2). However, even though yoga was seen as a mental journey, there is some evidence that the body could be used to achieve restraint using mantra (Sutra 1.27-28), asana (Sutra 2.46-48), pranayama (Sutra 2.49-53) and pratyahara (sutra 2.54-55). Using them gives the aspirant some tools to gain self knowledge and awakening. It is clear that Patanjali’s yoga is about stilling the mind, however, these sutras are the beginning of the modern idea that the body can be used as a tool for awakening.

Sutra II.47: Perfection in asana is achieved when the effort to perform it becomes effortless and the infinite being within is reached.

BKS Iyengar (Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali)

As time passed, a highly competitive royal market put pressure on the elites to preserve one’s position, and therefore the idea of personal empowerment became highly desirable. Tantric ideas start to challenge some of the old religious orthodoxy. Coming from outside the priesthood, we see a shift from the mind into what Gavin Flood calls “the Tantric Body”. One doesn’t need to discard the material in order to be free of suffering, but transform it into what it could be; all done with the help of the qualified teacher.

The guru was not a new concept, and is noted in earlier scriptures as a teacher of doctrine and philosophy. However, in Tantrism, he took on a much more important position. After achieving a divine status, he then became the mode of transfer of divinity into the disciple. He was not only an enlightened human, but it is said in the Kularnava Tantra that the guru is the father, mother, God and Lord. It is through the guru, a ‘secret’ mantra and initiation nyasa (ritual) that a deity is installed into the disciple. Could this have been the beginning of the modern ‘yoga teacher’?

Most students of yoga tell me that there is more to yoga than the postures, and I agree. In tantra, when the body is transformed there is personal empowerment that is said to go along with it, and the devotee can move beyond the limitations of normal human existence. This sounds just like the ideas Patanjali’s talks about in the Vibhuti and Kaivalya padas.

Being human is chaotic and noisy, and filled with strife. What if a teacher, such as the tantric guru, could place the power of God into sounds and images that could be used in the quest for liberation and empowerment? It sounds like the perfect elixir to eliminate human suffering, end doubt and bring unlimited power. Using ideas found in the Yoga Sutras, tantra added more ways for the yogin to transcend the misery of the world.

I once sat in my yoga studio and chanted the Gayatri Mantra. At first it was awkward because I did not know the words. Over time, I lost myself in the song and became one with the words of the music. I believe this is the power of chanting. Even Patanjali’s sutra 1.28 says that japa on Ishvara’s sound form has power.

Powerful words repeated are made manifest. The Invocation to Patanjali is a perfect example of how Vedic, yogic and tantric ideas have merged; a ritual chant done in the Iyengar tradition to prepare for the receiving of the gifts of practice:

yogena cittasya padena vacam

To purify the mind (citta), purify the consciousness, Patanjali gave the science of yoga (yogena) to us. To purify our use of words (pada) and speech (vacca), he gave a commentary on grammar to us, so that our use of words and way of speaking is clarified, distinct and pure.

Malam sarirasya ca vaidyakena

To remove the impurities (malam) of the body (sarira), he gave us the science of medicine (vaidyakena)

yopakarottam pravaram muninuam

Let me go near the one who has given these things to us

… and the Invocation goes on to give the chanter an image to focus the mind.

In other words, “Let me get close to that one that can help me touch my own purity. Let me imagine Patanjali as I chant. Let him transfer divinity inside me through this chant.”

Like peeling the layers of an onion to get to the sweet inside, or the opening of a flower to expose the pollen, tantra provided a physical means to dive deeper inside the material and created an understanding of the inner landscape. Additionally, it provided the Hindu aspirant a new way to see matter and its subtle potential. In tantra, the disciple learns that the body can also be divine, a tool to move deeper toward the power within- removing the surface impurities. In essence, the body can become the temple of God.

Some scholars believe that the tantric mudra is virtually equivalent to asana. As I look at the different hand mudras, I can’t help but see a resemblance to poses such as trikonasana or swastikasana. Maybe this set the stage for the exploration of the ‘mudra of the body’? Father Joe, a Catholic Iyengar yoga teacher, often spoke of “finding the prayer” within each pose; that place of open limitlessness that can be witnessed when one is inside a pose; free from the boundaries of the outer body.

Hinduism has been around for millennia, and its philosophies have shifted, changed and expanded. Yoga is no different, and so therefore we can respect its roots, study them for their value, but learn that the belief and practice of today comes mostly from Tantric sources.

Consequently, yogic teachings have moved away from being on the fringes of society as more people learned to read and write, opening the door to works such as the Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP), Shiva Samhita and Gheranda Samhita. These are the most recent books in the yoga library and they pay attention to the practice of yoga. In chapter 1 of the Hatha Yoga Pradiipika, the author Svatmarama shares that “Hatha-yoga provides a refuge for those afflicted by various types of suffering. Like the tortoise who holds up the world, hatha-yoga provides support for those practicing different forms of Yoga” (HYP 1.10). This is a great passage that marries both Patanjali’s yoga of the mind, and how the yoga of the body can be used to provide support.

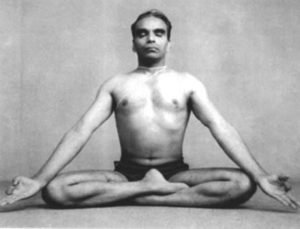

These three books include names of asanas that most modern yoga teachers would recognize, and the benefits of the poses. For example, in verses 35-43 of the HYP, siddhasana is said to purify the 72,000 ‘tantric’ nadis, or energy channels, and if the yogin meditates upon the atman, the ultimate goal or aim will be achieved. We can definitely see the entanglement of Tantric and Patanjali’s yoga philosophies within these texts. Where Patanjali offers only a brief glimpse into the subject of asana (2.46-48)), or pranayama (2.49-53), the Pradipika and two Samhita’s elaborate and provide direction as to how asanas, mudras and pranayama are to be performed. In essence, these modern yoga texts give people greater access to the ideas that Patanjali touches upon by offering them a preparation to what is now considered raja-yoga; Patanjali’s ‘stilling the mind’.

Samkhya gave an analysis and understanding of the world and one’s position in it.

Shankaracharya’s Vedanta taught us the influence of ignorance and non dualism. Patanjal gave us the philosophy of yoga: why we need it, what can be achieved, how it can be effective and the type of practice that is to be done. Tantra gives us the understanding that the body can be used as preparation for the higher spiritual practices that Patanjali discusses, regardless if we take the final step: transcending the world. Finally, the later texts elaborate on the early limbs giving poses and their benefits.

The marriage of these Hindu teachings has given modern humans the tools to bring Patanjali’s teaching of stilling the mind into our lives through the obvious and subtle layers of our material existence. Yoga is like the lotus that comes from nowhere under the water, and opens into the most beautiful flower. The paradox is that moving into our bodies has given us a way out.

In addition, based on comments from my professor, I wish to add further distinctions that need to be made clear:

“There is no description of non-seated postures in yogic texts until about 1,000 years ago, so Patanjali’s reference to asana simply means sitting (the literal Sanskrit meaning of the word). Although recitation of Om is mentioned, along with holding the breath, there’s not a physical practice of the sort seen today – the aim is detachment from the body to rest in consciousness. It’s therefore perhaps worth highlighting the main difference between Samkhya and the non-dual Vedanta most often linked with yoga in more recent centuries: for Patanjali, the goal isn’t union, but the opposite.” (Daniel Simpson, 2022)

According to Patanjali, prakriti and purusa are not ‘united’. They are separate entities, and need to be disentangled. Understanding this concept is kaivalya, or freedom, which the fourth pada highlights. However, depending on the underlying system the translation of “union” means oneness. In the Upanishads, it is the realization of connection. In Tantra, it is the fusion with the deities, and in hatha it is the balancing of energies.

Additionally, there is a distinction between the Vedic religion and the early Upanishads. The Upanishads introduce the concept of a cycle of births and the need to seek freedom from cyclical suffering. This is the first big shift in yoga history as the Vedas don’t mention these cycles. The next big shift is the introduction of Tantra and hatha, and then another just before modern yoga where postures become the primary focus instead of a preliminary. For example, the Gheranda Samhita only has 32 asanas, whereas BKS Iyengar’s “Light on Yoga” has approximately 200.